I began this design innovation series by looking at its history, and what it can teach about about designing for genAI. Last week, I began exploring the future of design innovation. I examined Design Thinking, a paradigm that has largely become synonymous with design innovation. The key takeaway was: Design is a practice, Design Thinking is a paradigm. Today, I focus on what’s ahead for design innovation. I examine other ways to practice design, and the role Design Thinking plays in this landscape.

Today’s episode draws on concepts from Design Thinking: Critical Analysis and Future Evolution, a 2021 article in the Journal of Product Innovation Management. Check it out to dive deeper on today’s topics.

Designing for an Ecosystem: Why We Need a Multi-Stakeholder Approach

Design Thinking began its rise to innovation management prominence around 25 years ago. Its growth coincided with a shift from technology primarily being used for workplace applications (e.g., early, bulky portable phones) to widespread consumer adoption (e.g., cellphone). Designing desirable user experiences and interfaces became increasingly important to create a product that a consumer would use everyday. Design Thinking was a playbook that designers and non-designers alike could understand and implement.

Since then, our technology has become significantly more advanced and intertwined. It's tablestakes that I can collaborate with others in a Google Doc in real-time, and set different sharing permissions with different people. My parter and I can both remotely control our Nest thermostat from our smartphones and smartwatches, respectively. A machine-learning-driven customer service chatbot analyzes the content and intent of my messages to provide a (hopefully) useful response.

In short, teams building technology are no longer “designing one thing for one person”, as Human-Computer Interaction scholar Dr. Jodi Forlizzi has observed. Instead, nearly everything being designed is a service or platform, designed for multiple stakeholders to interact with and through. Effectively designing new technologies requires a shift in audience focus, from “one end user” to “many stakeholders”. We can conceptualize this from left to right on this Audience axis:

Design Thinking, as applied in a product design context, has classically focused on one end user. There are other design paradigms that consider multiple stakeholders. For instance, Systems Thinking is a holistic paradigm that examines different ways that parts of a given system interact and influence each other within a whole. Applying this paradigm can help yield a robust solution that considers multiple perspectives.

Systems Thinking has been long adopted, for instance, by urban designers, considering how and where people (aka “users”) coexist with buildings, other people, policy makers, businesses and so on. Service Design (and related methods like service blueprinting) are specific Systems Thinking approaches that we can take to apply this multi-stakeholder lens to provide a multifaceted view of problem space.

Futures thinking is another paradigm that helps us consider a broader audience view. There are numerous approaches under the futures thinking umbrella (e.g., speculative design, anticipatory ethnography, foresight) that can help us explore, anticipate and plan for potential futures - including the ecosystems of people and technologies in each of those futures.

Considering multiple stakeholders is especially important with emerging technologies. Consider the first Google Glass. This early headset, despite being a compelling technological advancement, ultimately failed due to concerns around privacy violations (see the now-infamous “glassholes”). What if we had considered the needs of the non-glasses-owning bystander with equal weight as the end user? Or what potential futures might look like, in which the Glass was widely adopted? Would the device have had a different fate?

Problem Solving versus Sensemaking

Another key axis when considering the future of design innovation is the worldview you and your team adopt in the design process. This “Practitioner Worldview” axis has two poles: positivist and constructivist.

Positivism assumes that design problems exist “out there” in reality. This worldview implies we can understand and unambiguously identify these problems, given the right approach and tools. This is the worldview underlying Design Thinking.

For a positivist, a problem can potentially be well-defined (depending on the available information), and then solved. The probability of finding a successful solution relies on how thoroughly solution space is examined. Ideating and producing a large number of ideas (e.g., as in a Design Thinking ideation brainstorm) is therefore important under this worldview, boosting your odds of finding a successful solution.

In contrast, constructivism assumes that problems aren’t “out there” - they’re socially constructed. Everyone wears a lens through which to look at reality - meaning that different people look at things differently. The lens determines what is and isn’t relevant, how things connect, and how we interpret the design space.

The constructivist approach to design involves more than just understanding the problem. You shape - aka construct - the problem through interpretation. Consequently, the problem is co-created alongside the solution, such that the problem is an output of the design process. This stands in contrast to positivism, where the problem is an input. We can use approaches like participatory design to actively invite the people we are designing for into our process, to co-create knowledge through active involvement and collaboration.

Limitations of Positivism for Complex Problems

A positivist worldview can be helpful if you have a highly focused problem you’re aiming to solve. However, if you’re wrestling with complex problems, a positivist approach will be reductionistic, leading only addressing one small problem in a larger ecosystem, potentially harming the broader ecosystem in the process.

Consider the true story of Operation Cat Drop: In the 1950s, DDT was widely used in Borneo to reduce malaria-carrying mosquitoes. Another result of “solving” the mosquito problem was that local cats - which also controlled the rat population - were ultimately killed by DDT. The rat population surged out of control, leading to the Royal Air Force airdropping cats to correct the issue - a cautionary tale about unintended consequences of not considering the broader ecosystem before offering a solution.

Disruptive innovation is one flavor of complex problem, in which a technology solution disrupts existing markets while unlocking new opportunities (aka problem spaces) and therefore, markets. For instance, iPhone (solution) unlocked the opportunity to conveniently hail a ride from anywhere, spawning the rideshare market. Generative AI (genAI) is another solution unlocking new problem spaces. We need to consider the symbiosis between a solution and emerging problem spaces to design something that is both valuable and technically feasible (I’ll share more about this in my upcoming EPIC 2024 conference paper, Designing AI to Think With Us, Not For Us).

Another flavor of complex problem is the “wicked problems” (e.g., climate change, health care, education). These lack a definitive formulation and have no clear benchmark as to where you can stop solution-seeking, among other characteristics. These require careful consideration of the broader ecosystem and its potential futures, to ensure we don’t just preserve the status quo with our solutions.

Putting It All Together

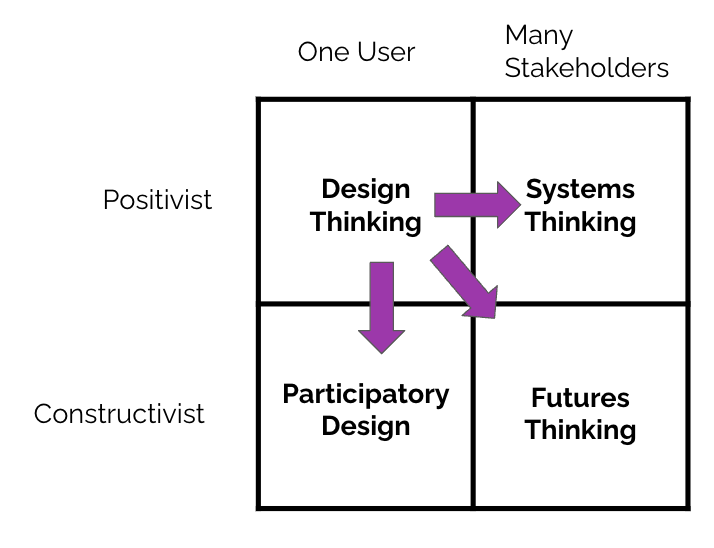

We can visualize the different design practices we’ve discussed on the following map, with our Audience x-axis and Worldview y-axis.

Design Thinking has traditionally been in the positivist, one-user-focus realm. Systems Thinking, while ultimately focused on problem-solving, takes a holistic, multi-stakeholder approach. Participatory design is a more constructivist approach, often applied with a group of target end users (though it can also be applied to involve multi-stakeholders, so consider this border to be somewhat fluid). Futures thinking takes a constructivist, multi-stakeholder approach. Given the complex design challenges we face (e.g., the disruptive innovation of genAI), design innovation needs to lean on constructivist, multi-stakeholder paradigms.

It’s worth mentioning that there’s also an aspect of sequencing how you apply these design paradigms. For instance, you might start with a Futures Thinking approach to inform your product vision and subsequent strategy. You can then map your broader stakeholder ecosystem and identify solutions that consider different needs (i.e., Systems Thinking). You might then employ participatory design to co-create knowledge and solutions. Where, if at all, does Design Thinking fit?

If you have a well-defined problem without your broader problem set, Design Thinking may be applicable. Design Thinking’s rapid prototyping and testing approach can also be helpful when evaluating and refining potential solutions.

Takeaways

The future of design innovation looks like considering the broader ecosystem for which we are designing, as well as potential futures for that ecosystem. This is especially important when designing for disruptive technologies (like genAI solutions) and working with wicked problems. Partner with your friendly neighborhood design researcher, business anthropologist or design strategist (or other folks versed in the practices discussed today) to:

Consider Multiple Stakeholders: Move beyond designing for a single end user to consider multiple stakeholders to create robust solutions that address diverse perspectives and needs.

Adopt a Constructivist Approach: Use Futures Thinking approaches to envision potential futures and work backwards from desirable futures. Embrace practices like participatory design that involve co-creating knowledge to better navigate complex and evolving problem spaces.

Integrate Diverse Design Practices: There are many ways to practice design, and the “best” approach depends on where you are in your process (e.g., how you approach developing a vision is different from developing a strategy, which are both different from product design execution). Consider sequencing or blending different approaches depending on your context, to form a comprehensive approach to innovation.

Sendfull in the Wild

I’m excited to be participating in EPIC 2024, August 18-21. EPIC is the premiere international conference on ethnography in business and organizations, and it’s their 20th anniversary this year. I’ll be presenting my paper, Designing AI to Think With Us, Not For Us, as part of a session on Crafting Research Futures. I’ll also be part of a panel on Ethnography in AI Product Development, joined by leading UX practitioners Lee Cesafsky, Rebecca Knowe, Larry McGrath and Anoop Sinha. Get your tickets here.

Human-Computer Interaction News

Virtual reality (VR) training for physicians aims to heal disparities in Black maternal health care: A VR training series being developed for medical students and physicians teaches them about implicit bias in their communications with their patients who are people of color and how that affects race-based health care disparities. Read the full paper here.

How culture shapes what people want from AI: Stanford researchers explore how to build culturally inclusive and equitable AI by offering initial empirical evidence on cultural variations in people’s ideal preferences about AI. Read the full paper here.

Google pulls Gemini AI ad from Olympics after backlash: The ad showed a father using Gemini (genAI tool) to help his daughter write a letter to her hero, American hurdler Sydney McLaughlin-Levrone. If genAI is supposed to give us back time for more genuine human interaction (like writing a heartfelt letter with your child), this ad showed the opposite, outsourcing this special task to genAI. Stay tuned for a future episode, where I share a tool for determining if and when to offload tasks to genAI.

Is your team building an emerging technology product? Sendfull can help with customer discovery, concept validation and building a product evaluation plan. Reach out at hello@sendfull.com

That’s a wrap 🌯 . More human-computer interaction news from Sendfull next week.