ep. 40: Design Thinking - One of Many Ways to Practice Design

8 min read

I started this series on design innovation by looking at its history, and what we can apply from that history when designing for generative AI (genAI). Last week, we looked at design innovation in present practice, sitting down for an interview with design leader and technologist, Jordan Harvey, CEO and founder of Remote Control. Today, I start unpacking where design innovation is headed.

I’ll examine Design Thinking, a paradigm that has largely become synonymous with design innovation - and, as I’ll discuss - the very practice of design itself. I explore how Design Thinking rose to dominance, and its strengths and its limitations for the design challenges of today, and why it’s important to view Design Thinking as one of many ways to practice design.

I’ll continue this discussion next week, looking at other paradigms like Systems Thinking and Futures Thinking, if, when and how Design Thinking can fit alongside these paradigms, and what this means for teams building emerging technology products.

Design Thinking’s Rise to Power

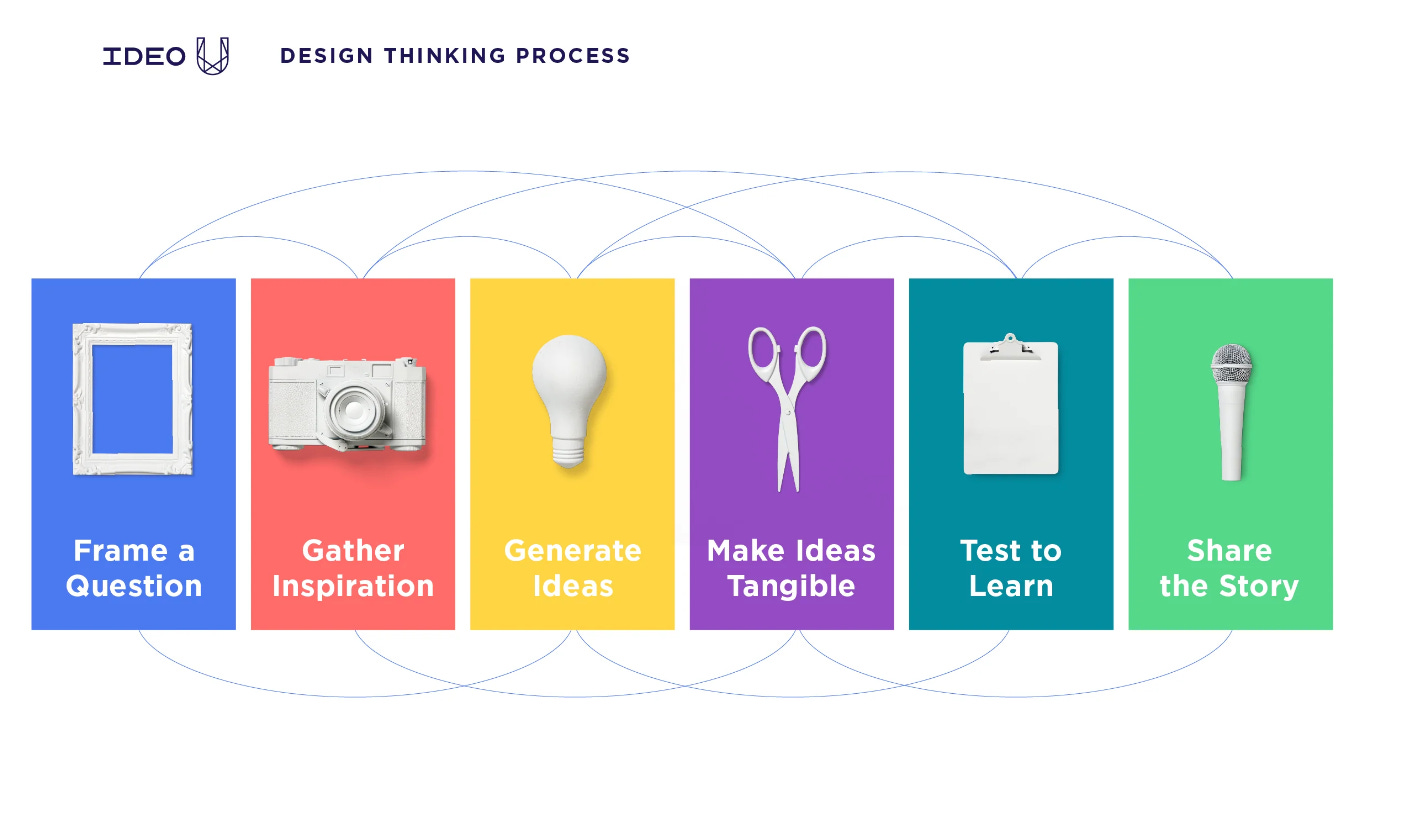

Design Thinking (DT) is “a human-centered approach to innovation that draws from the designer’s toolkit to integrate the needs of people, the possibilities of technology, and the requirements for business success.” This definition comes from Tim Brown, Executive Chair of IDEO, a key figure in establishing DT (more here).

Tim’s 2009 book, Change by Design: How Design Thinking Transforms Organizations and Inspires Innovation, alongside Roger Martin’s 2009 book, The Design of Business: Why Design Thinking is the Next Competitive Advantage were highly influential for establishing DT as a widely accepted innovation paradigm, with worldwide adoption in the business world. Giants like Netflix, AirBnB and UberEats are a few examples of the many companies that have implemented DT to solve problems for customers. In parallel, DT has solidified as a research stream for innovation management scholars.

DT has strong roots in the design philosophy that emerged from Stanford University starting circa 1957. This philosophy was grounded in humanistic psychology that emphasized the uniqueness of the human individual (i.e., the primordial ooze for “user-centered design”), interdisciplinary collaboration across social science (e.g., psychology), the humanities (e.g., art) and technology (e.g., engineering), and learning through rapid prototyping and feedback. These practices yielded countless inventions that started to shift this design philosophy towards the world of business.

A shift in business context around 25 years ago marked the tipping point that moved DT from an innovation paradigm centered around Stanford University to global prominence. Technology moved from something for specific workplace applications to widespread consumer use. “User experience” and “user interfaces” became a necessary part of designing a product that a consumer would choose to use everyday. Companies building technology therefore needed a paradigm with a playbook that designers and non-designers alike could understand and implement. The two 2009 books on DT delivered on these demands.

Something critical happened during DT’s widespread adoption: Design thinking became synonymous with design.

One of Many Ways to Practice Design

Design is a practice. Design Thinking is a paradigm.

This distinction is laid out in this comprehensive, 2021 Journal of Product Innovation Management article, which unpacks key themes in a special issue on DT. They define design as activity that we practice with the goal of addressing an “area of problems”, pointing to two key definitions:

“Design is about devising courses of action aimed at changing existing situations into preferred ones.” - Nobel-prize-winning social scientist, Herbert Simon

“Design is making sense (of things).” - Content analysis pioneer, Klaus Krippendorff

In short, design happens. Design does not imply a specific tool, method or process, whose effectiveness needs to be tested. There are many ways to practice design. A given paradigm - like DT, is one possible way to practice design.

The distinction resonated with me, because it helps make sense of the criticisms leveled against DT in recent years. For instance:

DT focuses on existing problems and therefore remains trapped in an “incremental design trajectory”, often solving problems of the past, rather than imagining a new potential futures.

Relatedly, DT “preserves the status quo”, often leading to superficial solutions that don’t address deep-rooted systemic issues (e.g., falling short when designing sustainable urban infrastructure, future-proofed against climate change).

Paraphrasing Dr. Lilly Irani, Associate Computer Science Professor at UC San Diego: DT positions the design practitioner as empathetic mystics, uniquely capable of translating the efforts and experience of the community, especially those of lower-level workers, into capitalistic opportunity.

These criticisms have culminated in headlines tolling the death knell of DT, such as “the era of design thinking ends” (Fast Company - who was tolling a similar knell back in 2011). I see these criticisms resulting from businesses holding DT above all other possible paradigms - as the way to do design to foster innovation. As a result, DT gets applied to challenges where it isn’t the best fit (see the case study of New York’s Dryline wall for more) or applied at the wrong timescale (e.g., during strategy formation rather than during product execution). This is especially true in cases where a team is staring down the nose of disruptive innovation or wicked problems (e.g., climate change, education design, health care), which lack a definitive formulation and have no clear benchmark as to where you can stop solution-seeking, among other characteristics.

The key point is that DT - and its accompanying toolkit - is one of many we can apply to practice design. It may have applicability in some contexts and timescales (i.e., I still see value in its toolkit when in the trenches of non-gen-AI product development, for instance, for rapid prototyping and testing) but not others - and that’s ok.

There are many design practitioners who are well-aware of this, having applied valuable practices from Futures Thinking and Systems Thinking paradigms to drive innovation and address wicked problems in business contexts for decades (more on these paradigms and their underlying philosophies next week).

My quick explanation of why these paradigms haven’t taken off in the same way as DT is that they: (a) are higher in complexity, moving beyond problem solving for a given end user, (b) require prioritizing long-term thinking (i.e., not something the human brain excels at, and often less incentivized in business, relative to meeting the next quarter’s KPIs) and (c) involve building a effective strategy - a nontrivial challenge that many companies struggle with (see Roger Martin’s recent Five Deadly Strategy Myths).

Next week, we’ll look at the other ways to practice design, as well as if and how we can sequence DT with these other paradigms to meet the needs of current and future design challenges.

Takeaways

Design is a practice. DT is a paradigm - one of many ways we can practice design. We should not assume DT is the default, especially in an age where we are building gen-AI-powered platforms and services capable of increasingly advanced “thinking tasks”, intersecting with urgent needs for sustainable and responsible solutions.

Now, introducing other paradigms (more on these next week) is its own change management activity, given DT’s 25+ years of traction. As design practitioners, we have the opportunity to lead discussions about if, when and how DT can be applied, and continue to raise awareness about how other paradigms (e.g., Systems Thinking, Futures Thinking) can bring value to both product strategy and execution.

In my own practice, it has sometimes been valuable to apply DT with other paradigms, depending on the nature and stage of the project. For instance, if I’m working with a team at project outset trying to formulate a product vision (and subsequent strategy), Futures Thinking - a paradigm with associated methods like foresight - helps us explore potential futures and identify desirable future(s). We can then identify the milestones required to bridge the gap between the current and future state. Once you start ideating on specific product concepts for shorter term goals, DT can often help guide ideation, prototyping and testing (there are exceptions, especially when working with genAI, as I’ll talk about in an upcoming paper).

Finally, there are some fundamental, general tenets that birthed DT (e.g., interdisciplinary collaboration, generally keeping customer needs in focus) that remain relevant. Design practitioners need to keep exploring (and documenting!) how we can adapt these to our evolving product development practices - for example, having social scientists, artists and engineers work hand-in-hand to develop useful, desirable genAI-based solutions.

Stay tuned for more on the future(s) of design innovation next week.

Sendfull in the Wild

I’m excited to be participating in EPIC 2024 in a few weeks. EPIC is the premiere international conference on ethnography in business and organizations, and it’s their 20th anniversary this year. I’ll be presenting my paper, Designing AI to Think With Us, Not For Us, as part of a session on Crafting Research Futures. I’ll also be part of a panel on Ethnography in AI Product Development, joined by leading UX practitioners Lee Cesafsky, Rebecca Knowe, Larry McGrath and Anoop Sinha. Get your tickets here.

Human-Computer Interaction News

Development of 'living robots' needs regulation and public debate: Researchers at the University of Southhampton are calling for regulation to guide the responsible and ethical development of bio-hybrid robotics - a science which fuses artificial components with living tissue and cells. Read the full paper here.

New video test for Parkinson's uses AI to track how the disease is progressing: A video-processing technique developed at the University of Florida uses AI to help neurologists better track the progression of Parkinson's disease in patients, potentially enhancing their care and quality of life. Read the full paper here.

AI’s Impact on Black Americans: Stanford’s Institute for Human-Centered AI shared an interview with Dr. Sanmi Koyejo, assistant professor of Computer Science at Stanford. Koyejo is a co-author of an important white paper shared earlier this year, “Exploring the Impact of AI on Black Americans”.

Is your team building an emerging technology product? Sendfull can help with customer discovery, concept validation and building a product evaluation plan. Reach out at hello@sendfull.com

That’s a wrap 🌯 . More human-computer interaction news from Sendfull next week.