ep. 66. Reflections on What Computers Can (And Still Can’t) Do

7 min read

“Technology is driving the future… it is up to us to do the steering”. - Slogan of the Computer Professionals for Social Responsibility, co-founded by Terry Winograd.

Last Thursday, the Berkeley Institute of Design shared their weekly newsletter announcing the next guest in their seminar series - and I did a double take. The speaker? Terry Winograd, Professor Emeritus of Computer Science at Stanford.

If you work in human-computer interaction (HCI), you’ve likely encountered Terry’s work. He founded Stanford’s HCI Group and led it for two decades, helped launch the Hasso Plattner Institute of Design (the d.school), and is widely known for his contributions to natural language understanding and a human-centered approach to AI system development.

After some quick calendar reshuffling - and managing to grab the last slot for a 1:1 chat with Terry - I dove into prep for Tuesday. Central to his upcoming lecture, What Computers Can (and Still Can’t) Do, was the 1986 book he co-authored with Fernando Flores: Understanding Computers and Cognition.

The book’s central argument was that “Good Old-Fashioned AI” (GOFAI) was destined to fall short - not just technically, but ethically - because it failed to account for the situated, embodied, and relational nature of human cognition. Terry’s upcoming talk would revisit this argument, given the success of large-language models (LLMs) - aka the “new AI”, which are based on different techniques than GOFAI.

In today’s newsletter, I share my top three takeaways for product teams designing AI systems, based on my concentrated deep-dive into Terry’s HCI x AI insights.

Takeaway 1: Care, Even Over Efficiency

“The trouble with artificial intelligence is that computers don’t give a damn”.

Terry offered that quote by philosopher John Haugeland, both in Tuesday’s Q&A and his 2024 article, Machines of Caring Grace. AI systems may appear intelligent, but they lack concern about us human users.

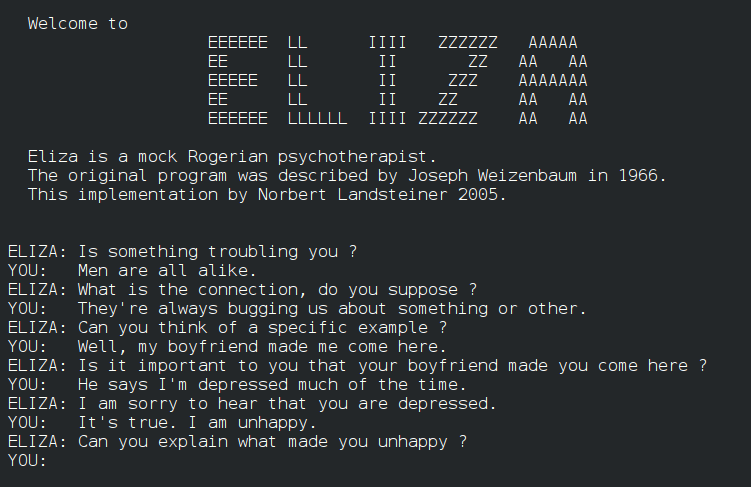

This can be easy to forget - our natural tendency to anthropomorphize AI can obscure its limitations. It doesn’t take much - let’s look at ELIZA, an early natural language processing computer program, developed by Joseph Weizenbaum at MIT in the mid-1960s.

Dubbed ‘the world’s first chatbot’, ELIZA - an extremely simple system compared to current generative AI tools like ChatGPT - sometimes fooled people into thinking they were talking to a human. According to legend, while testing ELIZA, Weizenbaum’s secretary asked him to step out of the room - the conversation with the chatbot had become unexpectedly personal.

We often prioritize efficiency when designing AI systems (sidenote: see episode 64 for a human factors take on why designing to “increase efficiency” often has the opposite effect). However, prioritizing efficiency over care can lead to AI systems that are indifferent to human values, relationships, and lived experience.

Efficiency-driven AI often overlooks the social and emotional dimensions of interaction - what it means to be human. When systems are designed without concern for care, they risk reinforcing harm or loneliness (more in this recent study by OpenAI and MIT), even if they perform their tasks effectively.

This is why we need to focus on designing for care, even over efficiency. What might this look like? AI systems designed to support human relationships, not replace them. As designers of these systems, let’s start by asking: What kind of collaboration do we want to foster? What would it look like to design for collaboration? Care?

Sidenote, “Care, Even Over Efficiency” is structured following Matthew Ström’s shortcut to good design principles - Even Over statements. But that’s for another newsletter.

Takeaway 2: Behind Every System Is a Worldview

The first third of Understanding Computers and Cognition is essentially a philosophy primer. It includes coverage of:

The rationalist tradition, in which knowledge is gained through reason and logical deduction.

Heidegger and phenomenology, the study of how we make meaning of the world through our direct, lived experience.

Hermeneutics, the study of interpretation.

Why is so much airtime given to philosophical “traditions” in what appears to be a computer-science-flavored book? Because the design of AI systems is grounded in assumptions about human cognition, language, and meaning.

One of my favorite quotes from Understanding Computers and Cognition: “In asking what computers can do, we are drawn into asking what people do with them, and in the end into addressing the fundamental question of what it means to be human”. I like this quote because it demonstrates that we can’t separate the development of AI systems from these philosophies that underly that development, especially as AI capabilities continue to advance.

A rationalist worldview - that intelligence is just reason, divorced from embodied experience - leads to building an AI system to this spec of “intelligence”. While it may be technically impressive, it’s disconnected from how people make sense of the world. What does it look like to include a more phenomenological approach, acknowledging the role of embodiment and lived experience? Terry and I discussed the role AI-enabled AR wearables might play, given that they’re more contextually aware than traditional interfaces, and therefore, more “embodied”.

What worldview - aka philosophical tradition - underlies the AI systems that you’re working on? How might we design these systems in ways that reflect and support the embodied, situated nature of human cognition?

Takeaway 3: Sense, Steer, Adapt

Can we predict exactly where AI is headed long term? No. What, then, can we do to shape its development? Steer.

This point goes back to the quote at the top of the article, “Technology is driving the future… it is up to us to do the steering”. We must stay attentive and responsive to how AI is developing, and steer it to preferable futures.

Terry referenced Fernando Flores’s metaphor of navigating a whitewater raft: we don’t control the river, but we can learn to steer. Designing for AI means learning to guide systems in motion - sensing, steering, adapting - even when the destination isn’t fully known.

Teams building AI systems can think of this approach as an ongoing practice of sensemaking and course correction. Build feedback loops that keep you close to how customers are actually using your system. Design for adaptability: prioritize mechanisms for updating models, refining interaction patterns, and incorporating evolving user insights.

In fast-moving terrain, the most resilient teams aren’t the ones with the most detailed roadmap - they’re the ones most prepared to respond wisely when the water changes.

Further Reading

Check out this short primer on the topics we covered today:

Understanding Computers and Cognition (1986): Book by Terry Winograd and Fernando Flores.

Machines of Caring Grace (Dec 2024): Terry’s Boston Review response to Evgeny Morozov’s “The AI We Deserve”.

AI Ethics (Sept 2024): Terry’s guest lecture at the University of Ottawa.

Sendfull in the Wild

I’m excited to be teaching a tutorial with EPIC People on Designing AI to Think with Us, Not for Us: A Guide to Cognitive Offloading, happening May 7. Join me for this half-day course to learn strategic tools and cognitive science expertise you need to drive insights, design, and decision making that empowers people and builds trust.

Everyone is welcome to register and EPIC members get $50 off: https://www.epicpeople.org/project/5725-designing-ai-cognitive-offloading/

Human-Computer Interaction News

The New “USB-C for AI”: The Model Context Protocol (MCP) is an open protocol that standardizes how applications provide context to LLMs. MCP matters for HCI because it enables greater interoperability across apps, as AI models can now connect with outside data sources and services without requiring unique integrations for each service.

Nurture More Important than Nurture for Robotic Hand: Researchers at the University of Southern California found that tactile sensors are less important than the order of learning experiences for embodied AI.

How AI and Human Behavior Shape Psychosocial Effects of Chatbot Use: MIT and OpenAI studied how AI chatbot modes (text, voice) and conversation types affect user well-being. Voice chatbots initially eased loneliness and dependence, but heavy use across all types increased emotional reliance on AI and reduced real-world social interaction.

Designing emerging technology products? Sendfull can help you find product-market fit. Reach out at hello@sendfull.com

That’s a wrap 🌯 . More human-computer interaction news from Sendfull in two weeks!