ep. 53: Designing Future Systems

5 min read

“I visualize a time when we will be to robots what dogs are to humans, and I'm rooting for the machines.” - Claude Shannon, Father of Information Theory

Is Shannon’s potential future a desirable one? What would it look like? How can we choose to design technology where we can harness “the machines” (think personalized interfaces or design tools that accelerate our iterative process), while retaining our human agency?

These are the questions my new UC Berkeley graduate course, Designing Future Systems, will be tackling in Spring 2025.

Systems Thinking as Career Future-Proofing

In last week’s episode, I covered how systems thinking is essential for future-proofing careers, especially for roles that directly touch UX - from designers and researchers to product managers and engineers. That skill set includes rapid framing and reframing problem space from multiple stakeholder perspectives and altitudes, anticipating potential future scenarios, and critically assessing the societal impacts of emerging technologies.

These are the skills that I’ll cover in Designing Future Systems, including frameworks and toolkits from systems theory, strategic foresight, and speculative design. Through course projects, students will practice methods such as systems mapping, scenario planning, horizon scanning, diegetic prototyping, and anticipatory ethnography.

We’ll tie these skills to developing human-centered emerging technologies, with a strong focus on addressing the foundational challenges that generative AI’s rapid, solution-first momentum poses to building systems that benefit individuals and society. I’ve been referring to this as designing AI to think with us, not for us.

Developing Taste Among the Machines

A key question that follows from focusing on systems thinking is, how do practitioners cultivate taste when we’re all just orchestrating the big picture? If you can jump into a design tool to AI-generate a multitude of high-fidelity screens with a few clicks (or insert multimodal input here), how can you tastefully art direct them without the hours spent honing visual design skills?

My answer: We must create a stronger connection between the concrete and the abstract from Day 0 of UX education. Let me explain.

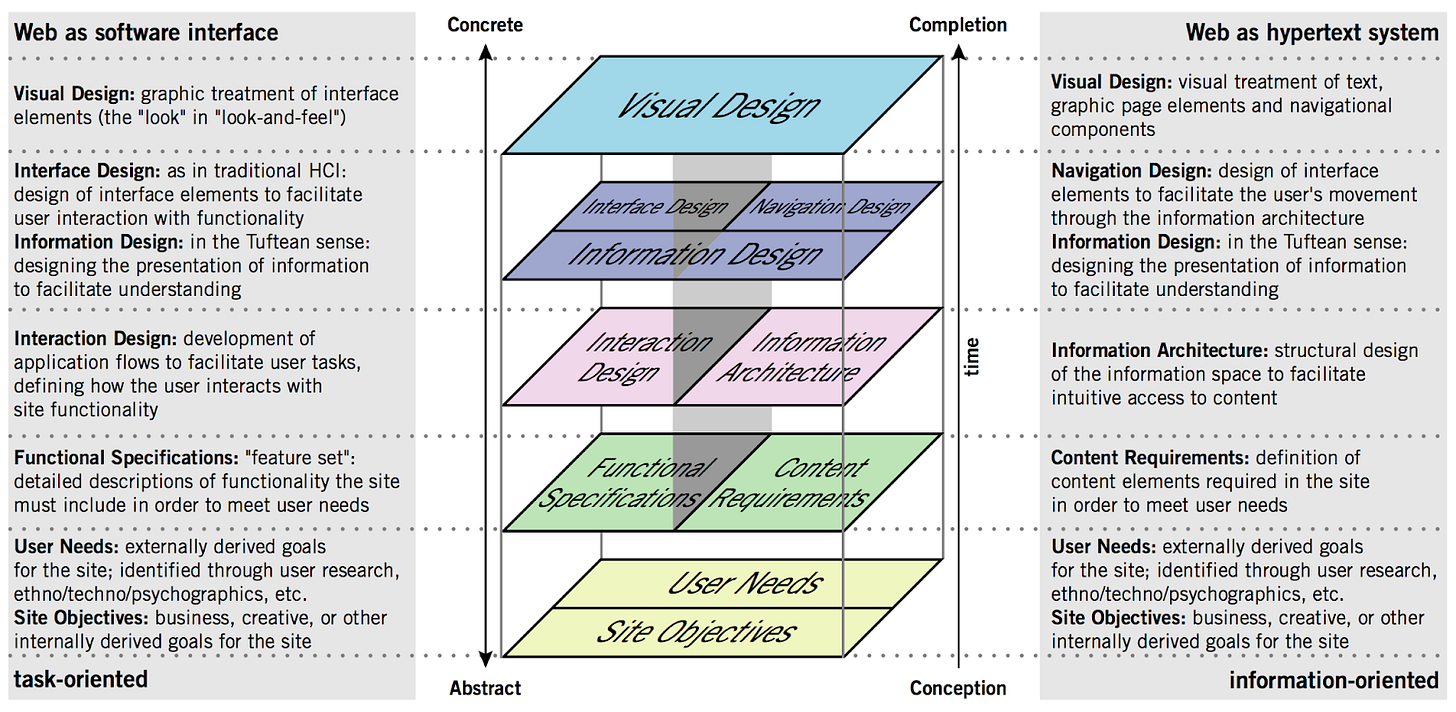

Jesse James Garrett’s seminal Elements of UX describes the five elements that comprise UX design, from the abstract to the concrete: user needs, functional specifications, interaction design, interface design, visual design. Put another way, these elements are: strategy, scope, structure, skeleton, and surface.

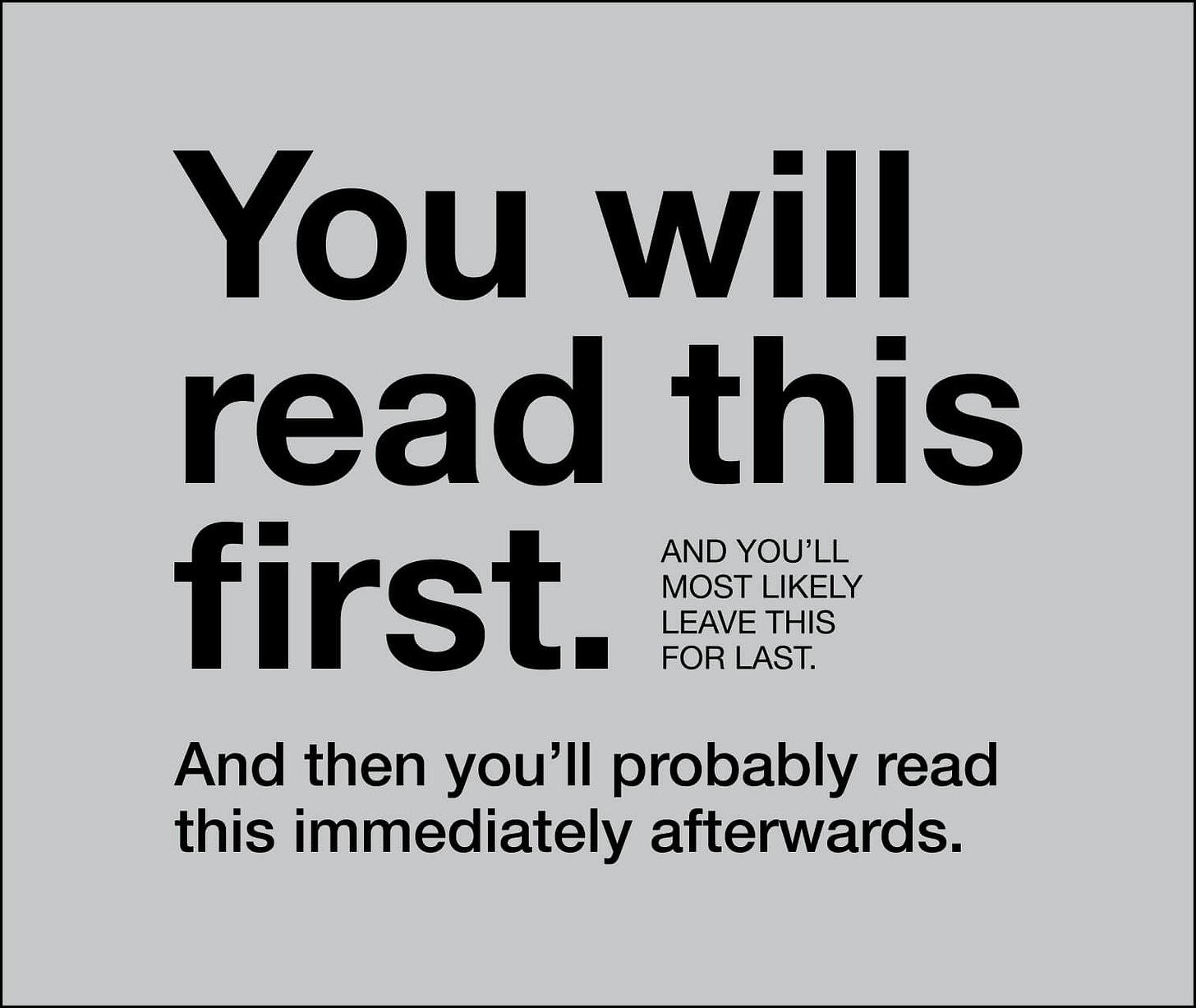

A common perception when students walk into my Intro to UX Design class is that UX is the “look and feel” of a design solution. A key “ah-ha” moment each year is when students see the connection between their choices of visual design principles and elements, and a user’s goals and needs. A simple example is hierarchy:

“You will read this first” is grabbing the user’s spotlight of attention, and should be in service of helping the user do what they need to do in your design solution to meet their needs. We need the “abstract” user needs foundation to successfully implement this visual design principle, and periodically zoom out from tactical work to make sure the layers of UX are interacting as intended.

Similarly, when you can generate an interface with one click, it’s meaningless unless it aligns with the user’s needs - not to mention generic-looking if you cannot creatively tweak the visual design in service of user needs.

In this way, AI is just accelerating a tipping point for UX. The challenge of connecting the abstract with the concrete has been around since we could easily forgo sketching in favor of jumping into Photoshop (or Figma). It’s now just on steroids, given the scale (and speed!) at which AI is increasingly able to automate the more concrete parts of our workflows.

I’m not suggesting we obviate the study of the concrete either. For instance, I’d argue it’s still important for designers to understand how color theory works, to mold AI-generated clay into a tasteful, unique shape.

However, we can't rely on “concrete” alone.

This reality is reflected in the trend of smaller art and design schools closing - we need a curriculum change to face an increasingly complex, interconnected technology landscape (for more, check out this podcast with HCI professor Jodi Forlizzi and information architect Jorge Arango).

Takeaways

We need systems thinking to future-proof UX careers.

My new course, Designing Future Systems, is my way of addressing what I see as an urgent need for the next generation of technology teams to think critically about the implications of their technology on individuals and society.

This shift towards systems thinking doesn’t mean budding UX practitioners should ignore the foundational, concrete skills of UX. Instead, UX educators and mentors should emphasize how the concrete (e.g., visual design) connect to the abstract (e.g., user needs), helping students build systems thinking skills early on.

🚀 Sendfull in the Wild: C100 Workshop

As a Canadian living in the Bay, it was extra special to lead a workshop for Canada's most promising scale-stage tech companies in the C100 Growth Program. I shared tools for scaling companies to structure, focus and reframe their customer learning goals, part of the Sendfull Customer Understanding Toolkit. I’m excited to keep in touch with these amazing teams.

Designing emerging technology products? Sendfull can help you find product-market fit. Reach out at hello@sendfull.com

That’s a wrap 🌯 . More human-computer interaction news from Sendfull next week.