When I graduated from my Psychology PhD program at the University of Toronto, I didn’t know user experience research (UXR) was a career option. My worldview was that you go on from grad school to complete at least one post-doc, get on tenure track, and eventually, become a university professor for life. This is why it was especially meaningful to be invited to share my career journey last week, at the University of Toronto Mississauga’s Psychology Colloquium.

Today, I share some key learnings from my talk. By the end of this episode, you’ll be equipped with actionable takeaways on how to translate your academic skills to industry.

What does a UXR do?

As a UXR focused on emerging products, I help teams navigate ambiguous product areas and build useful, usable products for anticipated markets. A key part of my role is helping define problem space for a given product: the conceptual landscape where we explore, understand and frame a particular problem we want to solve for people. Once we have a design solution, I lead research to evaluate whether we’re solving the problem that we think we’re solving, and offer recommendations on how to iterate based on people’s feedback.

This is all done in an extremely collaborative setting - as I’ve previously discussed, UXR (and Design in general), is very much a team sport. For your research to have impact, you need to work with your team (many of whom are unlikely to have a formal research background) to learn business context, the decisions that need to be made, timelines and constraints. You keep them involved throughout the entire research process, and follow up long after your study has concluded, to help the team integrate findings into product development.

As a Psychology graduate student many years ago, this description would have seemed daunting. How do you even get into this field? Which of my skills - if any - are translatable? While I’ve discussed aspects of my career journey in this Meta AR careers piece, what I share here goes into more detail, both from learnings from my time as a research scientist, and insights that have emerged after founding Sendfull and teaching UX at Berkeley.

From academia to industry

Takeaway 1: Find the common link between your academic work and industry roles.

When I transitioned from graduate school into industry at an augmented reality (AR) start-up called DAQRI, I didn’t go directly into UXR. The first stop along the way was research science.

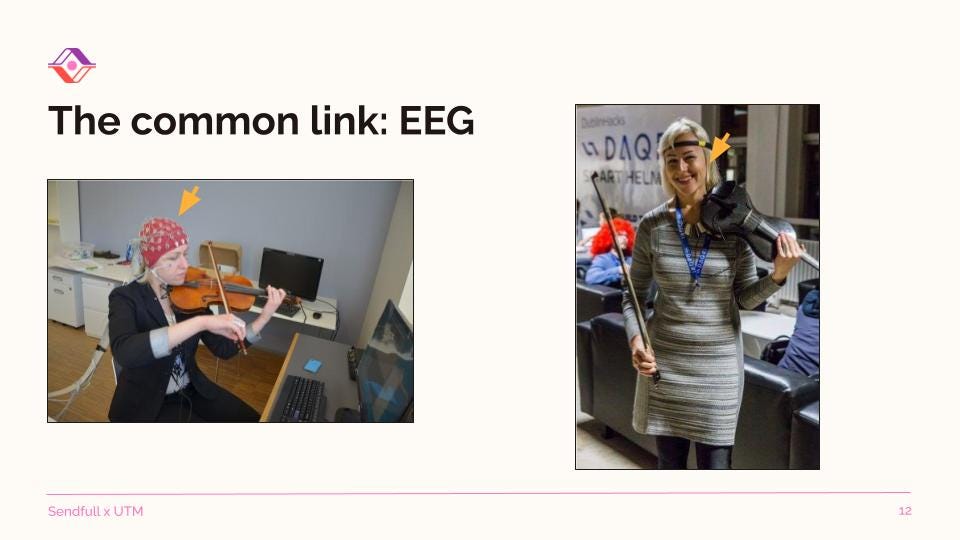

When I decided that I wasn’t going to continue on to an academic postdoc in cognitive neuroscience, I interviewed for a research science position that called for a neuroscientist’s skill set. The team’s goal was to integrate a brain computer interface (BCI) into AR wearables, to monitor field engineers’ attentional states (think getting a notification that it’s time for a break, based on a real-time analysis of your neural activity showing a drop in attention). As such, my academic background using electroencephalography (EEG) - a method to record an the brain’s electrical activity - throughout my graduate research made me well-positioned to take on this role.

This was the first takeaway from my talk: if you’re considering moving from academia to industry, before even homing in on the function you’re interested in (e.g., UXR), find that common link between your academic work and industry (in my case, EEG).

Takeaway 2: Learn about how products are made.

As a newly minted industry research scientist, I found myself writing up patents on the use of neurophysiological signals as user interfaces for AR products, often collaborating with product designers. Long days and nights brainstorming in meeting rooms led not only to several patents, but also learning the nuts and bolts of product design.

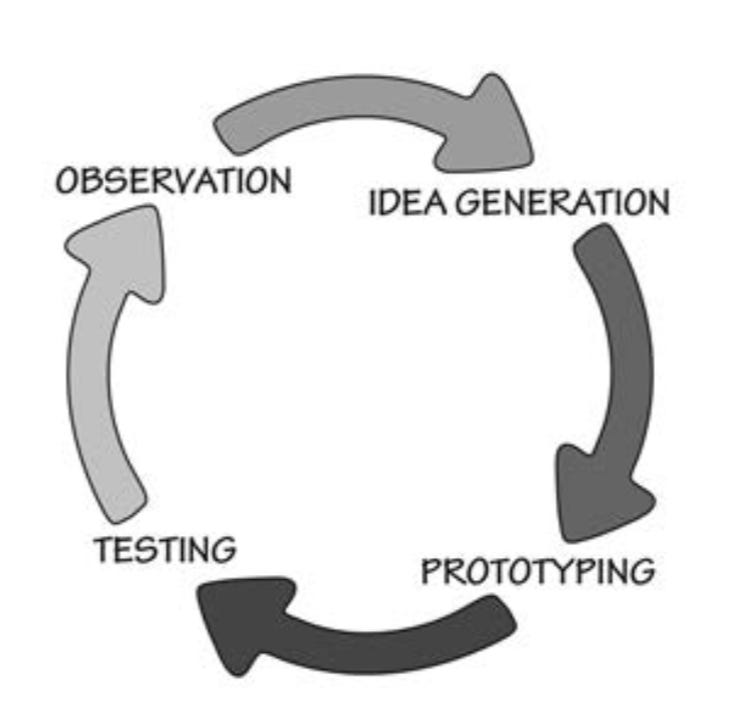

I was introduced to the interactive process of human-centered design, and as introduced to the classic UXR handbook, Observing the User Experience by Elizabeth Goodman, Mike Kuniavsky and Andrea Moed. These introductions helped me see how research and development could translate to product, and revealed that my background in human cognition was extremely relevant to the world of product design.

Through collaboration with product designers, I also learned about the near-term challenges they were facing - for instance, deciding how to design embodied interfaces for AR headsets, going beyond 2D elements (e.g., buttons, lists) we’ve come to expect on flat 2D screens. Armed with my new UXR handbook, I helped the team run their first formal usability test. This turned out to be useful to the team. Before I knew it, UXR became my full-time role. I switched over to the product side of the company, led research to build the company’s first case studies, and taught other team members about what I was doing.

Summing this up, learning about how products are made was instrumental in helping me discover how my academic skills could translate, how to be helpful to my team, and how to frame these skills in a way others in industry would understand. If you’re looking for a general primer about how products are built, I recommend Eric Ries’s book, The Lean StartUp. If you want to deep-dive on UXR, check out Observing the User Experience (second edition).

Takeaway 3: Get familiar with qualitative research.

If you’re a student interested in UXR, and haven’t practiced qualitative research, I recommend getting started as soon as possible. As a cognitive neuroscientist in a Psychology department, I had an outsized focus on quantitative research methods. Hypothesis testing - a statistical method used to determine if there is enough evidence in a sample data to draw conclusions about a population, was the reigning epistemological tool. Putting it politely, qualitative research was not regarded with the same esteem.

Imagine my surprise, learning that to answer questions about “how” and “why” people do things (like use products!), qualitative research was critical. Later in my career, when I would go on to work with anthropologists and sociologists, I would come to develop a deeper appreciation for qualitative research, and saw how narrow my previous focus on hypothesis testing was.

If you’re interested in transitioning into UXR from a discipline that does not regularly use qualitative methods, my advice is to familiarize yourself with qualitative research, both in academic (e.g., cultural anthropology, sociology) and industry contexts (e.g., Practical Ethnography: A Guide to Doing Ethnography in the Private Sector by Dr. Sam Ladner, IDEO U).

Takeaway 4: Keep up on tech news and get hands-on to build intuition.

At this point in my career, I was recruited to join Adobe, on the founding team for Adobe Aero, an AR authoring app. This meant switching focus from field engineers using AR hardware and software in architecture, engineering and construction, to creative professionals building AR experiences, primarily for mobile devices.

To ramp up to this new space, I spent a lot of time reading and doing, to learn this new landscape. On my commute from Palo Alto to San Francisco, I would spend my time reading Twitter, Tech Crunch, Medium, and speciality publications like AR Insider. I spent time learning the basics of 3D and immersive tools like Blender, Adobe Dimension and Unity, to develop intuition about these mediums. I had almost every mobile AR app I could get my hands on installed on my phone.

I often get asked if you need a background in computer vision or another technical field to break into the extended reality space as a UXR. My answer is no - but I will advise you to immerse yourself in the technology landscape, and develop that intuition about user experiences, both from a consumer and creator perspective.

Takeaway 5: Practice telling the story of your findings - it’s key to success as a UXR.

Putting several years of work into one sentence, I would go on to lead UXR not only for Aero, but for the new Adobe Substance Suite, before leading mixed reality research at Meta for Quest 3. Across this time, I learned the importance of what I call “accurate storytelling”. You can have the most beautiful, rigorous UXR report in the world, but if you’re not telling the story of your findings, “marketing” your learnings to key stakeholders, and working with your teams to integrate your findings, that report may as well not exist.

This is fundamentally different from academia, where we spend most of our time on the “methods” slides of our decks. In industry, methods sections are brief, if not relegated to the Appendix. It’s assumed you’re a strong researcher and know your methods - that’s why you have your job. This focus on storytelling and landing impact was a mindset shift, coming from academia. As an academic researcher coming to industry, you must accept that rigorous research and influencing people can harmoniously coexist. Telling a story, grounded in your solid research, is the key to this process.

If you’re new to storytelling, I suggest starting with this Harvard Business Review article, How to Tell a Great Story. From there, there are various free and paid courses you can take (I personally enjoyed IDEO U’s Storytelling for Influence, bringing a UX-specific lends to the craft).

In closing

Putting my five takeaways for the academia-industry transition in one place:

Find the common link between your academic work and industry roles.

Learn about how products are made.

Get familiar with qualitative research.

Keep up on tech news and get hands-on to build intuition.

Practice telling the story of your findings - it’s key to success as a UXR.

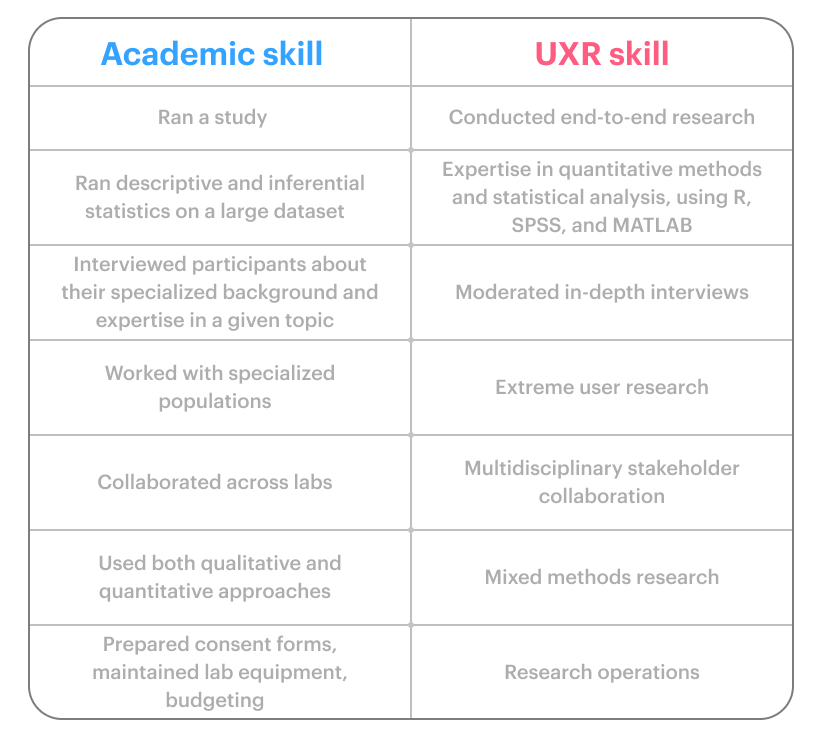

The overarching takeaway is that students of psychology (and any other field deeply rooted in the study of human behavior and cognition) have many skills that are transferable to UXR. You just need to translate and adapt them to an industry setting. The takeaways I’ve shared here are a starting point for that transition.

Human-Computer Interaction News

Scientists create AI models that can talk to each other and pass on skills with limited human input: Scientists at the University of Geneva modeled human-like communication skills and the transfer of knowledge between AIs, so they can teach each other to perform tasks without a large amount of training data (read the original Nature article here).

Robot, can you say 'cheese'?: Columbia University's Creative Machines Lab published a paper on Emo, a robot that anticipates facial expressions and executes them simultaneously with a human. It has even learned to predict a forthcoming smile about 840 milliseconds before the person smiles, and to co-express the smile simultaneously with the person. This advancement aims to make human-robot interaction more natural and build trust between humans and robots, with the potential to offer people companionship and assistance.

Universal brain-computer interface lets people play games with just their thoughts: Engineers at the University of Texas at Austin have created a brain-computer interface that doesn't require calibration for each user, making it more accessible and easier to use across different people. This foundational research holds potential for widespread clinical applicability.

Looking to set up an effective tech transfer process? Sendfull can help. Reach out at hello@sendfull.com

That’s a wrap 🌯 . More human-computer interaction news from Sendfull next week.